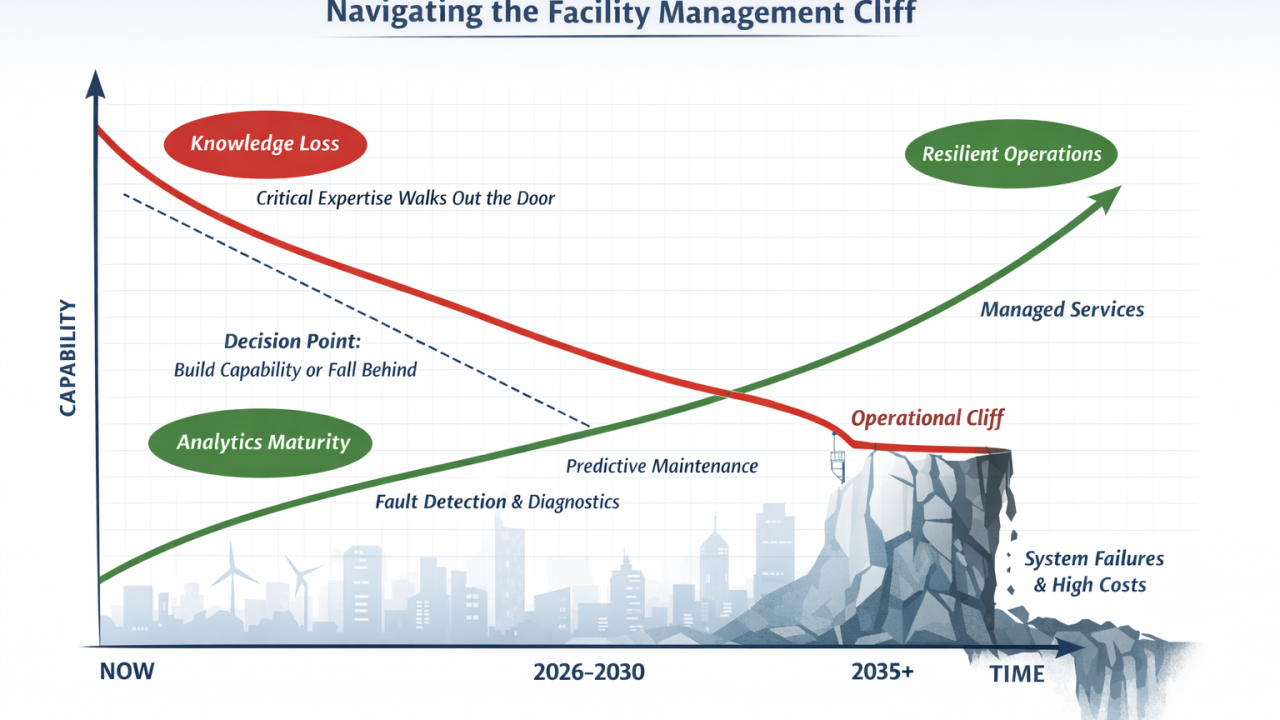

Scott Lannigan’s "hill and cliff" metaphor resonates because it already describes what many property portfolios are experiencing. Facilities management skills are tightening just as boards continue to demand operational improvement, stable tenant comfort, and defensible ESG reporting.

Deloitte’s Commercial Real Estate Outlook reports that around 50% of CRE leaders rank skilled operations staff shortages as a top-three risk, while more than 60% plan to invest further in automation and analytics in response. The underlying question becomes unavoidable: how can the impact of the strongest engineers be extended without simply adding headcount?

The myth that “we’ll just hire” is a strategy

A headcount-led response is effectively a wager against demographics. While individual vacancies may be filled, building deep senior capability in HVAC, controls, and BMS across an entire portfolio is becoming structurally difficult.

Scott Lannigan describes the downstream effect clearly: preventative maintenance slips, reactive work increases, and operating expenditure rises. Over time, that drift becomes visible in asset ratings, green lease discussions, and renewal negotiations.

There is also a growing key-person risk. When one experienced operator resigns or retires, undocumented control logic and hard-won “tribal knowledge” often leave with them. In an audit context, that risk is increasingly difficult to justify.

Dashboards without an operating model just add noise

Many portfolios are already stuck in what could be described as “pilot purgatory.” We see this pattern appear repeatedly across portfolios, including those operating at institutional scale. Huge amounts are invested across multiple pilots over 18 to 24 months, yet none scale beyond three or four buildings. Each pilot requires bespoke integration, ongoing supervision, and an internal champion (who often departs before year two).

EY’s Global Real Estate surveys show that approximately 67% of investors now treat ESG performance as a core investment criterion, yet only around 33% trust the quality of their building performance data. Fragmented pilots push portfolios toward that outcome by preventing standardisation of naming conventions, governance, and workflows.

Scott Lannigan’s practical benchmark is instructive: analytics and monitoring can reduce reactive work orders by 20% to 40% and allow experienced engineers to oversee two to three times more floor area. Those gains do not come from alerts alone. They come from consistent, repeatable decisions backed by evidence.

From technology upgrade to managed expertise

McKinsey analysis suggests that advanced analytics and remote operations can reduce building energy use by 10% to 20% and O&M costs by up to 20%. That margin becomes real only when teams stop hunting for problems and start closing them systematically.

NABERS and Property Council of Australia analysis shows that high-performing 5-6 star offices often use about half the energy of typical mid-rated buildings, reflecting 30% to 40% gains achieved over time. Whether performance is measured through NABERS, LEED, Green Star Performance, or BCA Green Mark, the principle is consistent: operational discipline compounds over years, not weeks.

Guidance from the Investor Group on Climate Change (IGCC) indicates that operational energy typically represents 60% to 70% of emissions in Australian property portfolios. Achieving the 30% to 40% reduction required this decade to align with a 1.5°C pathway is difficult to accomplish through hiring alone.

Smart buildings do not remove people from the equation. They determine where scarce expertise creates the most value.

How the CIM Partner Program extends expertise

Our Partner Program is built on a straightforward premise: engineering time should be spent on judgement and decision-making, not manual data collection. Partners combine the PEAK Platform with the expertise of their building performance engineers to scale outcomes without relying on an increasingly limited pool of senior talent.

Increased scale and productivity

Partners use analytics and fault detection capabilities to centralise the first layer of performance review across multiple sites. Instead of logging into several BMS front ends, teams work from a single prioritised queue with evidence attached.

This shift makes the two-to-threefold increase in floor-area coverage realistic. Junior engineers are not expected to become seniors overnight; early data alignment establishes the foundation for a workflow that supports repeatable, portfolio-wide decisions.

New recurring revenue streams

The ‘workforce cliff’ that Lannigan describes also presents a commercial challenge for engineering firms. Revenue models built around project spikes remain vulnerable to labour shortages, tender cycles, and staff turnover.

Partners address this by building monitoring and optimisation retainers around PEAK, supported by monthly or quarterly performance reviews, fault detection, and action plans. The value proposition shifts from “we fixed it once” to “we keep it fixed,” which aligns more closely with institutional asset manager expectations.

Greater energy savings and ratings resilience

Energy and ratings performance continue to matter as energy prices remain volatile. A single Sydney CBD tower drifting 5% can incur tens of thousands of dollars in additional annual energy costs, before accounting for complaints or tenant churn.

Knight Frank’s recent APAC tenant research shows that around 50% of occupiers now rank operational performance and smart building capability among their top leasing criteria. That creates a direct link between analytics, tenant retention, and asset valuation.

Improved client retention

Mandates are rarely lost due to lack of activity; they are lost when activity fails to translate into visible outcomes. Partners maintain client confidence by providing access to real-time dashboards and periodic reports that link actions directly to results.

This transparency changes asset management conversations. Opinions are replaced with shared priorities based on impact, risk, and tenant exposure.

What the operating model looks like in practice

Consider an A-grade office where HVAC complaints spike every second summer while the site team remains stretched. PEAK continuously ingests BMS and meter data, flagging issues such as after-hours plant operation, unstable temperature control, or dampers that fail to close.

In most markets, contractor performance often determines whether analytics deliver outcomes or merely generate alerts. Even advanced FDD platforms fail without accountability for triage and verified close-out, including 48-hour SLAs for critical alerts. Yet many RFPs still focus on BMS integration while overlooking workflow redesign, proof-of-fix standards, and performance-based incentives.

Effective SLAs reflect the work itself. Where digital workflows enforce these standards, 60% to 70% of high-impact faults are often converted into verified fixes within 30 days. Without them, resolution rates frequently remain below 20%.

The business case: expertise over headcount

A superfund-backed owner managing more than 100 assets faces a familiar decision. One option is to hire five to six senior FM and engineering roles at fully loaded costs, hoping the labour market cooperates.

The alternative is to invest annually in portfolio analytics combined with managed optimisation support delivered through partners. Over a five-year horizon, the headcount-heavy approach often struggles to fully staff roles, while performance remains dependent on a small number of individuals.

By contrast, the partner-plus-analytics model more reliably standardises routine decisions and concentrates senior expertise on the issues that materially affect outcomes. Across composite portfolios, this approach commonly delivers 10% to 15% energy savings alongside more stable ratings, often translating into several million dollars in cumulative operating expenditure savings.

When senior engineers are still spending time chasing alarms rather than driving outcomes, the workforce cliff described by Scott Lannigan is already approaching.

Start climbing the hill while there is still time

Addressing the workforce shift does not require a sweeping transformation program. It requires acknowledging the demographic reality and adopting an operating model that does not depend on finding large numbers of highly experienced engineers.

The workforce cliff is a structural reality, not a temporary disruption. Portfolios that succeed will be those that extend expertise through systems, governance, and accountability before experience walks out the door.

.jpg)